Several popular internet claims assert that Jesus never existed as a human being, and that Christians simply adapted old pagan stories about gods such as Horus, Mithras, Krishna, Dionysus, Attis, and Osiris into the Christian religion by changing a few names. This idea became huge after the 2007 movie Zeitgeist, and continues to spread rapidly through short videos, memes, and social media posts.

It is evident that many people repeat this assertion without ever examining the original ancient writings or archaeological evidence. Because doing so would be time consuming and would undermine the entire anti-Christian narrative. Upon examination of primary sources, scholars find that long lists of identical details are almost entirely absent.

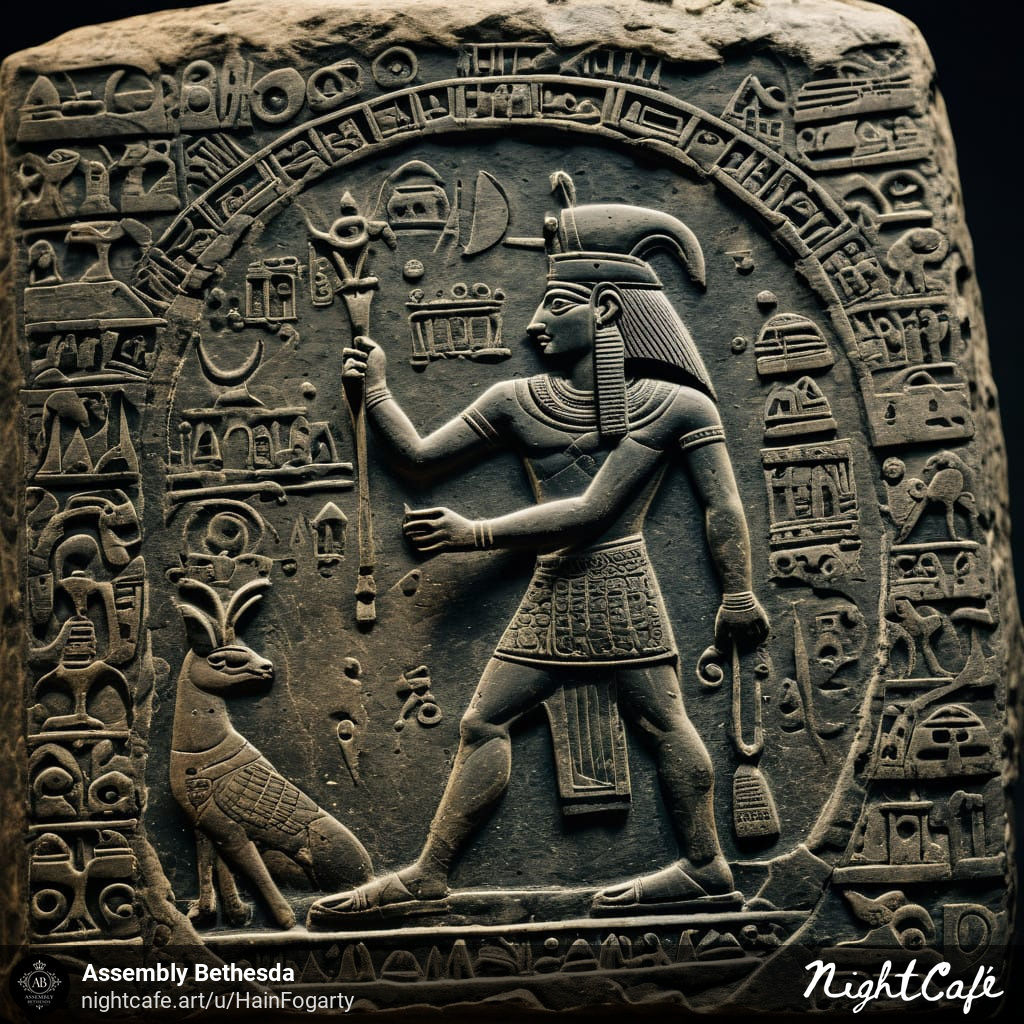

The Horus Story: What the Memes Say vs. What Egypt Really Believed

Internet memes usually present a neat list of “facts” about the Egyptian god Horus: born of a virgin on December 25, visited by three wise men, baptized at age 30, had 12 disciples, crucified between two thieves, buried for three days, then resurrected.

Ancient Egyptian records, including the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, Book of the Dead, and temple inscriptions, tell a very different story. As a result of Isis uniting with the reassembled body of her deceased husband Osiris to conceive Horus, the birth was not virginal in the Christian sense. The Egyptians never referred to Horus’s birthday as December 25, nor did they mention three wise men, shepherds, or stars.

In some depictions, Horus is accompanied by four minor deities called the “sons of Horus” or by 16 protective spirits, but never with twelve disciples. Horus was never nailed to a cross because crucifixion was a Roman punishment that never existed in ancient Egypt. The myth depicts Osiris being cut into pieces by the god Set; later versions depict Set fighting Horus and injuring him, but Horus is restored by magic, and there is no reference to a period of three days in the stories.

Several of today’s prominent Egyptologists, including Erik Hornung, Geraldine Pinch, Jan Assmann, and J. Gwyn Griffiths, agree that the popular Horus-Jesus parallels originate from nineteenth-century books that invented details.

The Mithras Story: What the Memes Say vs. What Roman Evidence Shows A common myth concerning Mithras is that he was born of a virgin on December 25th, he had 12 disciples who represented the zodiac, he performed miracles, shared a last supper with his disciples, and he died and arose three days later.

According to Roman Mithraic temples, reliefs, and inscriptions, Mithras emerged fully grown from solid rock, sometimes holding a torch and knife, without any mother or virgin involved. As early as AD 274, the date December 25 was associated with the sun god Sol Invictus, and was originally not connected to Mithras’ birth.

Mithraic initiates passed through seven degrees of initiation, symbolized by planets, and two torchbearer figures appear in every temple, making up seven or nine figures, never twelve. The surviving relief and text do not depict Mithras performing miracles for followers or eating a last supper. The most significant reason is that Mithras never died in any known version of the Roman cult, which means he had no death or resurrection story to compare with Jesus.

A number of Mithraism specialists, including Roger Beck, Manfred Clauss, and David Ulansey, have confirmed that the online lists contain significant errors.

Where Did December 25 Really Come From?

Jesus’ birth date is never specified in the Bible. The early Christians in Rome began celebrating December 25 around 336. They chose that date because it already marked the Roman festival of the Unconquered Sun and fell near the winter solstice, when days begin to lengthen. It was easier for new converts to join the Christian faith when a popular pagan holiday was replaced by a Christian celebration. Many Eastern churches have observed January 6 as the date for centuries.

When religions spread, it is common for a convenient calendar date to be selected, but it is not the same as copying the entire life story of Jesus from earlier gods.

What Scholars Actually Say Today

As an agnostic New Testament scholar, Bart Ehrman maintains that virtually every recognized expert in ancient religion rejects the notion that Jesus is a recycled pagan myth. According to Swedish scholar Tryggve Mettinger, who carefully studied dying-and-rising gods, a few ancient figures did return from death, but the details, timing, and meaning differ greatly from those recorded in the gospels.

Major reference works such as the Oxford Classical Dictionary and the Encyclopedia of Religion no longer consider copycat theory credible.

Why the Myth Keeps Spreading

As a result of being unable to read Egyptian hieroglyphs or Persian texts, nineteenth-century writers made wild guesses and made wild claims. The internet transformed the old errors into colorful charts and short videos. Later books repeated the same mistakes without checking sources. Shocking, simple claims spread faster than detailed corrections.

The Bottom Line

In the same way that it used Greek language, Roman roads, and Jewish scriptures to share its message, Christianity adopted some customs, calendar dates, and artistic styles from surrounding cultures. However, the core historical events of Jesus’ life, his teachings, crucifixion under the Roman governor Pontius Pilate around AD 30 and the claim that he rose on the third day don’t fit the stories of Horus, Mithras, Osiris, Attis, Adonis, or any other pre-Christian figure.

When the original texts, inscriptions, and artifacts are examined carefully, the detailed parallels that appear online are false, exaggerated, or completely invented. Reading ancient sources for yourself matters far more than forwarding the next viral meme.

Reference List:

Scholarly Views on Pagan Parallels and the Christ Myth Theory

Listed below are seven scholarly works that critically examine claims of pagan influences on Christianity, including parallels between Jesus and figures such as Horus, Mithras, or Osiris, as well as the broader “Christ myth theory”, which suggests that Jesus is a mythological construct. In order to ensure balanced, non-biased analysis, these selections emphasize academic rigor, peer-reviewed or university-press publications, and perspectives from agnostic, secular, and critical historians.

They represent mainstream scholarly consensus, which largely rejects strong pagan-copycat claims as overstated or chronologically implausible, while acknowledging minor cultural exchanges. Each entry includes full citation details for accessibility.

1. Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist? The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012. An agnostic New Testament scholar dismantles the Christ myth theory, arguing that alleged pagan parallels (e. g. , to Mithras) stem from 19th-century misinterpretations and lack primary-source support. Ehrman emphasizes Jesus’ historicity based on early Christian and non-Christian texts, viewing mythicist claims as fringe.

2. Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. The Riddle of Resurrection: “Dying and Rising Gods” in the Ancient Near East. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell International, 2001. A Swedish historian of religion analyzes “dying-and-rising” motifs in ancient myths, including Osiris and Adonis, but finds weak chronological and thematic links to Jesus’ resurrection narrative. Mettinger, a secular scholar, concludes that while resurrection themes existed, they do not substantiate direct borrowing by early Christianity.

3. Eddy, Paul Rhodes, and Gregory A. Boyd. The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007. These biblical scholars critique comparative mythology, rejecting influences from Horus or Attis on the Gospels as based on outdated scholarship. They use historical-critical methods to affirm Jesus’ core traditions as rooted in Jewish apocalypticism, not pagan syncretism, with evidence from extrabiblical sources.

4. Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: TandT Clark, 2014. A critical New Testament scholar and former agnostic addresses mythicist arguments, including pagan parallels to Dionysus and Mithras, as methodologically flawed. Casey argues for a historical Jesus through Aramaic linguistics and early sources, dismissing copycat theories as ideologically driven rather than evidence-based.

5. Smith, Jonathan Z. “Dying and Rising Gods. ” In The Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mircea Eliade, vol. 4, 521–27. New York: Macmillan, 1987. A University of Chicago historian of religion evaluates the “dying-and-rising gods” category (e. g. , Tammuz, Osiris) as a late construct with no clear first-century precedents matching Jesus. Smith’s secular analysis highlights how 19th-century comparativists exaggerated similarities for evolutionary theories of religion.

6. Ulansey, David. The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries: Cosmology and Salvation in the Ancient World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. A classics scholar reconstructs Mithraism using archaeological evidence, showing no virgin birth, 12 disciples, or resurrection motifs akin to Jesus. Ulansey’s work, grounded in Roman inscriptions, posits Mithraism as a post-Christian development in some regions, reversing claims of influence on the Gospels.

7. Nash, Ronald H. The Gospel and the Greeks: Did the New Testament Borrow from Pagan Thought? 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1992. (Originally published 1976.) A Christian philosopher surveys Greco-Roman influences, concluding that Mithraism “flowered after Christianity” and lacks substantive parallels to Jesus’ life or ethics. Nash’s updated edition incorporates critiques from classicists, advocating a Jewish-Hellenistic

Until next time: Be Blessed and Courage.