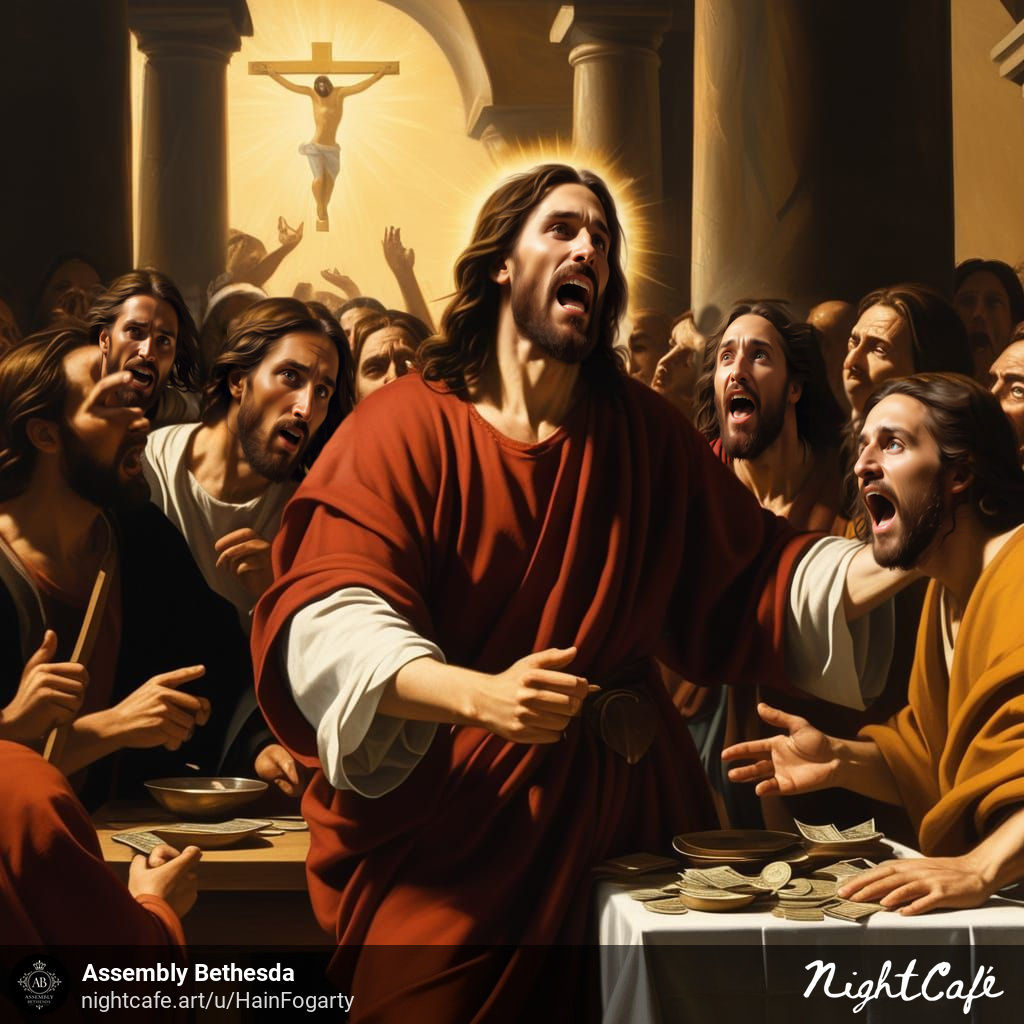

There is a dramatic scene in the New Testament that demonstrates the raw intensity of Jesus’ mission in its heart. In the event referred to as the Cleansing of the Temple, Jesus entered the sacred precincts of the Temple during the Passover festival and unleashed a torrent of righteous fury.

As he overturns tables, scatters coins, and drives out livestock with a makeshift whip, he confronts the merchants and money changers who had turned the holy courts into a chaotic marketplace. As echoed by ancient scriptures and challenging the religious elite to reclaim the purity of worship, this is not merely a tantrum, but a profound prophetic act.

As recorded in all four Gospels, the story provides a foundation for understanding Jesus’ zeal for God’s house as well as his intolerance for exploitation disguised as piety.

To grasp the full weight of this moment, consider the historical and cultural backdrop. As the epicenter of Jewish life, the Temple in Jerusalem was rebuilt by Herod the Great in order to awe and accommodate pilgrims from all over the world. A frenzy of activity was created during Passover as the number of worshippers swelled to hundreds of thousands. Devout Jews traveled from afar to offer sacrifices, doves for the poor, lambs for the affluent, but the system devolved into profiteering.

The priests authorized money changers to charge exorbitant fees for converting foreign coins into the Temple shekel, free of pagan images. Animal sellers inflated prices, ensuring religious hierarchy maintained steady revenue streams. In the course of time, what had begun as a practical service had transformed into a racket, taking advantage of the faithful and transforming a place of worship into a place of commerce.

Isaiah envisioned the Temple as a place of prayer for all nations. However, Jeremiah’s warning came true. It had become a den of robbers.

Even though the Gospel accounts are unified in essence, they provide nuanced perspectives that enrich the narrative. In John’s Gospel, the incident occurs during Jesus’ first Passover visit to Jerusalem, setting the tone for his confrontational manner. A vivid description is provided in John 2:13-16. Jesus surveys the temple courts in preparation for the festival, which are filled with cattle, sheep, and doves for sale and tables containing coins for exchange.

To herd the animals out, he fashions a whip from cords, not to lash people but to evoke their bleats and hooves throughout the colonnades.

In this version, coins clatter across the marble floors as tables collapse, and he thunders at the dove sellers, “Get these out of here, stop making my Father’s house a market.” A claim that the Temple belongs to Jesus’ Father unnerves the authorities and foreshadows his ultimate trial, highlighting his divine sonship.

According to Matthew 21:12 through 13, this action is swift and scriptural compared to the Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, in which the cleansing erupts during the climax of Jesus’ life, mere days before his crucifixion.

After entering the temple courts, Jesus drives out buyers and sellers, overturns money changers’ tables and dove sellers’ benches, and quotes the prophets directly, “My house will be called a house of prayer, but you are making it a den of robbers.” In chapter 11:15 through 17, Mark adds layers of resolution by stating that Jesus does not only disrupt trade, but also prevents goods from passing through the courts, effectively halting the flow of commerce.

As he addresses the crowd amid the uproar, invoking Isaiah’s inclusive vision, he decries the robbery. Luke’s rendition in 19:45 through 46 emphasizes the expulsion and the prophetic indictment, underlining the urgency of the situation.

There is scholarly debate over whether Jesus performed this act twice, once early and once late, or if John rearranged the chronological sequence for theological reasons. The repetition of this event across gospels indicates its centrality. As a result, Jesus becomes the true Temple, the one in which God’s presence is fully present, thereby rendering the stone temple obsolete. As a result of the upstart from Galilee, the religious leaders react with fury.

The question they ask in John, “By what sign do you do these things?” is a clear indication of their need for validation, yet Jesus points to his death and resurrection as the ultimate sign. The confrontation accelerates the plot against him, which weaves the cleansing into the Passion story.

It is a classic example of righteous anger, not impulsive rage, but a controlled blaze fueled by a love for God’s holiness. This represents the timeless relevance of the Cleansing of the Temple. Whether in sacred spaces or in society, Jesus provides an example of faith confronting injustice. In his dismantling of modern corruption, he echoes prosperity gospels peddling salvation for profit as well as institutions that hoard wealth while neglecting the vulnerable.

Worship demands integrity, prayer over transaction, community over isolation. For believers, it challenges a self-examination: are our gatherings true houses of prayer, or are they cluttered with distractions?

In reflecting on this episode, one sees Jesus not as a serene sage but as a revolutionary prophet, wielding disruption as a tool for renewal. Overturned tables symbolize a disruption of norms and scattered coins symbolize the fragility of ill-gotten gain. After passing through the Temple, pilgrims carried tales of a man who dared challenge the system, thereby establishing a new covenant. Soon thereafter, the Temple’s veil would tear, symbolizing access to God without human interference. In a world rife with commodified spirituality, Jesus’ whip-crack reminder invites us to return to the heart of faith, unadulterated and passionate.